Whilst proof reading the final draft for “What to believe (2)”, I had a flash of insight.

“Any account of events written more than 40 years later is likely to contain errors. Dates can become mixed up. Events can be forgotten. Others can be, albeit unwittingly, exaggerated. Details become blurred.”

Almost all accounts of historic events are written some time afterwards. It might be hours. It might be months. It might be decades. Major warships are a rarity in that someone on the Bridge will have the job of noting the time of significant events. The level of detail is impressive. The following is information from HMS Suffolk during the pursuit of the battleship Bismarck in May 1941.

04:47 – Enemy bore 186°, 15 miles, course 220°, speed 27-28 knots and bore 196° at 04:56.

A minute-by-minute account can be constructed. But when different accounts are compared, small discrepancies start to emerge.

The war diary of the Manchester Regiment was written daily. If the troops were in action at the time, the written record would have to wait. This accounts for some inaccurate spellings of place names. Reported casualty figures would be based on the best information to hand. Missing soldiers would often make their way back to their unit a few days later. This is a case of reporting too quickly for an accurate picture to emerge.

Guy Gibson’s personal account of Operation Chastise (the raid on the German Dams in 1943) was written a year after the events that he described took place. Many of the details were still secret at the time, and were to remain so until the early 1960s. Another barrier to accuracy.

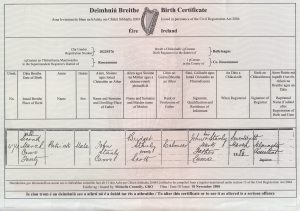

The relevance of the timing issue came to me when I re-examined my grandfather’s birth certificate. I have an official certificate.

It shows that the birth was reported by John, his father, who made ‘his mark’, thus indicating his illiteracy. I had always assumed that the information was contemporaneous. When it said ‘his mark’, I thought that this meant that John had made the actual mark that appears on the certificate. A reasonable assumption?

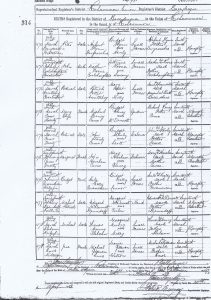

It transpires that the information on the certificate has been extracted from another register.

The small print at the bottom says that the register is a copy of the original. The handwriting is the same throughout, as one would expect under those circumstances. This means that the so-called marks are also copies. It has been countersigned to verify its’ authenticity by a third party. It is my understanding that the original document no longer exists. We do not know under what circumstances it was compiled. A total of seven births were registered on Saturday 17 March 1883. Six of those reporting a birth made a mark as opposed to a signature. Did the Registrar always fill in the original register whilst the informant was present, or were some events filled in later in the day, relying on memory for some of the details? If the latter, this may explain why the maiden name of my grandfather’s mother (shown as Bridget Scott) is different from that of his sister (shown as Bridget Ormsby) with whom he is staying in 1911.