Promotion can come quickly in times of war. Opportunities abound to show leadership qualities. There are many cases of men rising from Private to Lieutenant and beyond. Reaching the level of Major was possible. As previous articles have shown, the level of attrition of both officers and other ranks was high. As recorded in “Ancre”, the 2nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment was reduced to 6 officers and 150 men in November 1916. This represents an attrition rate of over 80%. Two years into the conflict, there were relatively small numbers remaining from the British Expeditionary Force that landed in France in August 1914. The experience gained by the survivors was invaluable. They were expected to help the drafts of new men that joined on a regular basis. And yet, Patrick Stanley stayed as a Private throughout. He didn’t even progress onto the first step of the ladder of promotion, that of Lance Corporal. To use the title of another blog, it is necessary to look at why as well as what.

Many of the men who enlisted, or were conscripted, would have held positions of some responsibility in civilian life. There would have been Foremen, Section Leaders, Shift Supervisors etc. There would have been captains of sports teams and those who had progressed in youth organisations (such as the Boys Brigade). Many of these men would have had a good basic education. School leaving age had been 14 since 1900. This means that everyone under the age of 28 should have benefitted from the new arrangements. Some of the men had more than a basic education. Some had stayed at school beyond 14. Others had attended evening classes to help them in their careers. Financial pressures at home often meant that capable young men were forced to take a job as soon as possible. Literacy levels had risen steadily in the decades leading up to the Great War. England claimed 97% literacy in 1900.

The situation in Ireland, as is often the case, was different. (A direct quote from another blog.) In 1901, overall literacy was 86%. It was higher in the cities and lower in the more remote areas. My Father said that Patrick wasn’t a fluent reader. Edith, his wife, would read any letters that arrived. Patrick signed his name on his enlistment papers. His signature in 1902 (when he originally joined) and in 1916 (when he was conscripted back) are recognisably the same. It is easy to see why his lack of education was a barrier to promotion in the Army.

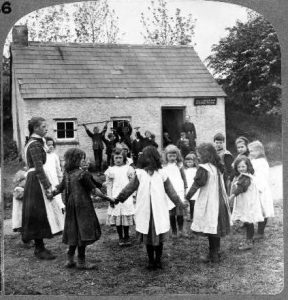

(Photo above: Connemara school in 1893. Note the absence of shoes for many of the children. Photo below: Monaghan school, early 1900s)

There is a note on his service record in November 1907. The month before he had been awarded Class I status, which entitled him to extra money. This didn’t last long. He was swiftly back to Class II. The note says ‘Education’. I am not sure exactly what this means. Perhaps the Army recognised that he needed help with the basics of literacy. Perhaps his fellow soldiers poked fun at his lack of education.

There is small sign that matters improved for Patrick. In June 1908 he was awarded a Good Conduct badge. Sadly, the old pattern re-emerged. Two months later he forfeited the badge. There are no further entries on his service record for the last two years of his peacetime service.

My father advanced another reason for Patrick’s lack of career advancement. He says Patrick positively refused promotion. Patrick felt that he would be put into a position where an order of his might cause the death of one of his soldiers. True story? We will never know. But he remained a Private.