Some historians call it the Battle of Passchendaele. Some call it the Third Battle of Ypres. The fact that three battles were fought in the same area is significant. It serves to emphasise the static nature of much of the Great War. Patrick fought in the Second Battle of Ypres, in 1915 (covered in ‘After Brighton’). He only missed the First Battle of Ypres in late October/November 1914 because he had already been wounded some 25 miles to the south. In 1917 he was about to take part in the Third Battle. The impact of the weather has already been discussed in ‘Bogs in Belgium’.

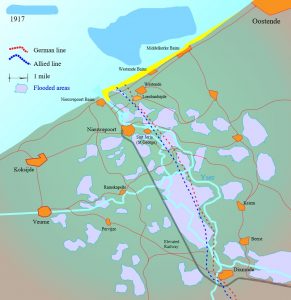

Patrick’s Battalion (2nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment) was primarily involved in holding a defensive line on the extreme north west end of the lines of trenches that stretched all the way to the Swiss border some 450 miles away. The trenches met the sea near to the town of Nieuport (Nieuwepoort in Flemish). The Yser river meanders across the very flat plain. The surrounding land is protected by a system of dykes and sluice gates. During the First Battle of Ypres, the sluice gates were deliberately opened on the orders of the Belgian King.

This turned the area into virtually impassable swamps. It halted the German advance. The map shows the extent of the flooding. Heavy rain merely exacerbated the situation.

The extent of the flatness of the land can be gauged by the photo below. It was taken from the top of the Yser Tower in Dixmude. The sea is about 10 miles away. The main fighting to capture Passchendaele took place another 8-10 miles further back.

The fact that the principle focus of the attack was a few miles away does not mean that this sector was quiet. The topography of the area meant that the opposing lines of trenches were often very close to each other. Simply moving up to take over a sector from another Battalion could be extremely dangerous. The trenches around Dixmude were known as the Trenches of Death. A section has been preserved.

The fact that the principle focus of the attack was a few miles away does not mean that this sector was quiet. The topography of the area meant that the opposing lines of trenches were often very close to each other. Simply moving up to take over a sector from another Battalion could be extremely dangerous. The trenches around Dixmude were known as the Trenches of Death. A section has been preserved.

The War Diary records that Patrick and his comrades were in trenches in the Lombardsijde sector (recorded as ‘Lombardzyte’, which is a curious hybrid of the French and Flemish spellings) from September 1st to 5th. In that time, one officer and 10 other ranks were killed by shell fire. Whilst both sides would seem to have accepted that this part of the line was likely to remain static, pressure was still maintained. If the main land battle plans had been successful, then an amphibious landing would have been attempted further up the coast. No such landing ever took place.

The trenches are about 10 miles from the billets in De Panne. To get there they would have marched. By the standards of other troop movements, this was a relatively short trip.

I found this photo in the Imperial War Museum collection. It shows the elevated section of the railway of the railway referred to on the map. The path of the railway can still be traced on aerial views. It has been converted into a cycle path. As such, it makes for a pleasant, and safe, way of travelling. Rather different to 100 years ago!